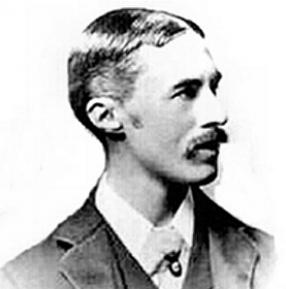

Alfred Edward Housman was born in Fockbury, Worcestershire,

England, on March 26, 1859, the eldest of seven children. A year after his

birth, Housman’s family moved to nearby Bromsgrove, where the poet grew up and

had his early education. In 1877, he attended St. John’s College, Oxford and

received first class honours in classical moderations.

Housman became distracted, however, when he fell in love with his heterosexual roommate Moses Jackson. He unexpectedly failed his final exams, but managed to pass the final year and later took a position as clerk in the Patent Office in London for ten years.

During this time he studied Greek and Roman classics intensively, and in 1892 was appointed professor of Latin at University College, London. In 1911 he became professor of Latin at Trinity College, Cambridge, a post he held until his death. As a classicist, Housman gained renown for his editions of the Roman poets Juvenal, Lucan, and Manilius, as well as his meticulous and intelligent commentaries and his disdain for the unscholarly.

Housman only published two volumes of poetry during his life: A Shropshire Lad (1896) and Last Poems (1922). The majority of the poems in A Shropshire Lad, his cycle of 63 poems, were written after the death of Adalbert Jackson, Housman’s friend and companion, in 1892. These poems center around themes of pastoral beauty, unrequited love, fleeting youth, grief, death, and the patriotism of the common soldier. After the manuscript had been turned down by several publishers, Housman decided to publish it at his own expense, much to the surprise of his colleagues and students.

While A Shropshire Lad was slow to gain in popularity, the advent of war, first in the Boer War and then in World War I, gave the book widespread appeal due to its nostalgic depiction of brave English soldiers. Several composers created musical settings for Housman’s work, deepening his popularity.

Housman continued to focus on his teaching, but in the early 1920s, when his old friend Moses Jackson was dying, Housman chose to assemble his best unpublished poems so that Jackson might read them. These later poems, most of them written before 1910, exhibit a range of subject and form much greater than the talents displayed in A Shropshire Lad. When Last Poems was published in 1922, it was an immediate success.

A third volume, More Poems, was released posthumously in 1936 by his brother, Laurence, as was an edition of Housman’s Complete Poems (1939).

Despite acclaim as a scholar and a poet in his lifetime, Housman lived as a recluse, rejecting honors and avoiding the public eye. He died on April 30, 1936, in Cambridge

"Farewell to barn and stack and tree,

Farewell to Severn shore.

Terence, look your last at me,

For I come home no more.

"The sun burns on the half-mown hill,

By now the blood is dried;

And Maurice amongst the hay lies still

And my knife is in his

side."

"My mother thinks us long away;

'Tis time the field were mown.

She had two sons at rising day,

To-night she'll be

alone."

"And here's a bloody hand to shake,

And oh, man, here's good-bye;

We'll sweat no more on scythe and rake,

My bloody hands and I."

"I wish you strength to bring you pride,

And a love to keep you clean,

And I wish you luck, come Lammastide,

At racing on the green."

"Long for me the rick will wait,

And long will wait the fold,

And long will stand the empty plate,

And dinner will be cold."

An Analysis of the Poem “Barn Stack and Tree”

The poem is from a whole book that Housman, the author, originally called "Poems of Terence Hearsay." Terence is the fictional speaker of most of the poems. He's an average person who lives on a farm in rural Shropshire and tells us stories (mostly very dark and depessing ones) about his own life and his neighbors.

The poet presents the incident in a typical ballad style which gives a dramatic effect to the situation. The poem is about a murder and the short dialogues and the repetition make it full of suspense and dramatic typical of Ballads.The murderer addresses the speaker who is called ‘Terence’. The reason for the murder is not clear. The poem seem to the climax of a fatal love affair involving 3 people. It is clear that the speaker or the man who committed the murder is shocked and in total despair. He decides to flee forever with the hope of not coming back. “ look your last at me, for I come home no more”. Terence or the friend of this unfortunate man tells us the story. So we can also call it a poem of confession.

Like all created worlds this one needs its myths, Housman very soon goes about providing them. 'Farewell to barn and stack and tree', which has Terence confronted by a man who has killed his brother, is actually a transformation of the story Cain and Abel. The unnamed Cain figure in the poem is, like his original, a "tiller of the ground", though we don't know if his victim Maurice kept the sheep (incidentally, though it may be unintended, there is certainly some irony in the note to the next poem in the book, which explains: "Hanging in chains was called keeping sheep by moonlight"). It is sometimes presumed by critics that the murderer in the poem is going to take his own life (or knows that the law will do it for him, since the next poem happens to be about a hanged man), but nothing in the poems actually tells us that. What lines like "She had two sons at rising day, / To-night she'll be alone" actually suggest, if one thinks, is the wanderings of Cain, the exile from the homeland. The difference between Housman's version of the myth and that in the Bible, is that his is a secularized rereading of it. The murderer answers to the sympathetic ear of Terence, not to the damning voice of the Lord.

The recognition of the parallel with the Biblical story emphasizes again Housman's underlying theme of the growth from innocence to discovery, for the poem clearly employs a myth which is a part of the archetypal pattern of loss of innocence, and the Eden-like setting, from which the youth is forced by his sin to leave, offers still another parallel with the creation myth.