Big Match 1983

Glimpsing the headlines in the newspapers,

tourists scuttle for cover, cancel their options

on rooms with views of temple and holy mountain.

‘Flash point in Paradise.’ ‘Racial pot boils over.’

And even the gone away boy

who had hoped to find lost roots, lost lovers,

lost talent even, out among the palms,

makes timely return giving thanks

that Toronto is quite romantic enough for his purposes.

Powerless this time to shelter or to share

we strive to be objective, try to trace

the match that lit this sacrificial fire

the steps by which we reached this ravaged place.

We talk of ‘Forty Eight ‘and ‘Fifty Six’,

of freedom and the treacherous politics

of language; see the first sparks of this hate

fanned into flame in Nineteen Fifty Eight,

yet find no comfort in our neat solution,

no calm abstraction, and no absolution.

The game’s in other hands in any case.

These fires ring factory, and hovel,

and Big Match fever, flaring high and fast,

has both sides in its grip and promises

dizzier scores than any at the oval.

In a tall house dim with old books and pictures

calm hands quit the clamouring telephone.

‘It’s a strange life we’re leading here just now,

not a dull moment. No one can complain

of boredom, that’s for sure. Up all night keeping watch,

and then as curfew ends and your brave lands

dash out at dawn to start another day

of fun, and games, and general jollity,

I send Padmini and the girls to a neighbor’s house.

Who, me? - Oh I’m doing fine. I always was

a drinking man you know and nowadays

I’m stepping up my intake quite a bit,

the general idea being that when those torches

come within fifty feet of this house don’t you see

it won’t be my books that go up first, but me.’

A pause. Then, steady and every bit as clear

as though we are neighbors still as we had been

In Fifty Eight. ‘Thanks, by the way for ringing.

There’s nothing you can do to help us but

it’s good to know some lines haven’t yet been cut.’

Out of the palmyrah fences of Jaffna bristle a hundred guns.

Shopfronts in the Pettah, landmarks of our childhood

Curl like old photographs in the flames.

Blood on their khaki uniforms, three boys lie dying;

a crowd looks silently the other way.

Near the wheels of his smashed bicycle

at the corner of Duplication Road a child lies dead

and two policemen look the other way

as a stout man, sweating with fear, falls to his knees

beneath a bo-tree in a shower of sticks and stones

flung by his neighbor’s hands.

The joys of childhood, friendships of our youth

ravaged by pieties and politics

screaming across our screens her agony

at last exposed, Sri Lanka burns alive.

Yasmin Goonaratne

An Analysis of the Poem “Big Match 1983”

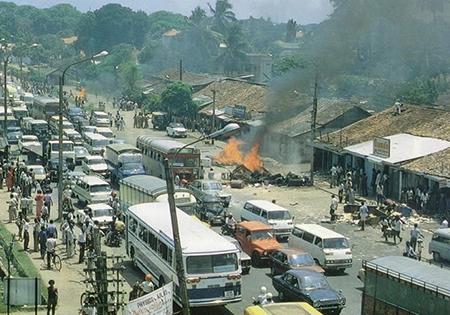

In the poem Big Match, 1983;Yasmine Gooneratne has registered her sorrow over the violent communal clashes which completely disrupted the diligently built cultural poetics of the multiracial and multicultural country. The violence of July 1983 was a moment of ignominy in the history of Sri Lanka for the ruling Sinhalese majority conducted an officially sanctioned pogrom against the Tamil minority. Even after the harrowing effects of the aftermath of the Second World War, humanity has failed to learn the importance of compassion and humanism. Though Sri Lanka had a rich cultural heritage, the discrepancy prevailing in society has ransacked the edifice of the cultural mosaic of a multi racial community.

Sri Lanka was granted freedom as a consequence of the struggle for independence in India. Indians forged with a single consciousness as a nation forgetting their inherent differences of language, religion and creed to gain freedom from the British but unfortunately there was no nationalistic credo among the Sri Lankans for freedom was granted to them. After their Independence from the British rule in 1948, the Tamil minority wanted their privileged position to continue but the Sinhalese majority wanted to tilt the balance to their advantage. This created a chasm between the two racial communities which resulted in sporadic outbreak of violence. In 1956 Sinhalese was made the official language which distressed the sentiments of Tamil populace. Racial sentiments became a poignant weapon in the hands of the power mongering politicians. In the 1970s the Tamil United Liberation Front clamored for a separate state called Elam.

Their radical ideologies, legitimization of terrorism, international involvement resulted in ethnic conflict which seems to be endemic. Of the Tamils, less than a half live in the North of Sri Lanka; the majority live among the Sinhalese. The Tamil minority enjoys a much better position in Sri Lanka than most minorities in other countries, and also, partly because of favored treatment ensuing from the classical colonial policy of “divide and rule” during a century and a half of British occupation, they became, in the words of Sri Lanka’s leading historian, K.M de Silva “a minority with a majority complex.” (Goonetilleke 450)

The violence of July 1983 created a sudden upheaval in the social constructs of Sri Lanka; suddenly multitudes were driven out of the country as refugees. The pathos is that the violence was targeted particularly against the Tamils, the ethnic minority. The commercial institutions belonging to the Tamils were selected and targeted. Suddenly Tamils in Sri Lanka were made paupers who had to flee to save their lives forgetting their heritage and the legacy of their fore fathers.

Media has sensationalized and commercialized the ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka for most of the newspapers Sri Lankan Cultural Poetics: Yasmin Gooneratne’s the Big Match 125 worldwide carried the horrific racial conflicts as the headlines. ‘Flash point in Paradise.’ ‘Racial pot boils over.’(4) Journalism has lost its ethical base: instead of creating an awakening about the need of brother hood, it converted racial conflict into best selling news item. The ethnic conflict is worldwide problems for most of the nations have become multiracial due to immigration. The solution to this conflict remains a nightmare for we have accepted the concept of universal brotherhood as a theoretical proposition but we have failed when it comes to practical implementation.

The ethnic crisis or racial problems are a watershed in the history of human civilization. Most affluent people affected by the racial violence left Sri Lanka for the Western countries for a better livelihood. The civil war in Sri Lanka created the largest Tamil diaspora in the world. Though they left their native country with bitter feelings and suffered from a sense of alienation. They hoped to reinstate new roots in the adopted country but when the civil war turned tumultuous they thanked their fortune for being alive.

And even the gone away boy

who had hoped to find lost roots, lost lovers,

lost talent even, out among the palms, makes timely return giving thanks

that Toronto is quiet romantic enough

for his purpose.(5-10)

The powerless citizens of Sri Lanka are in an absurd situation wherein they have to be objective and practical amidst irrevocable calamity. The innocent people who lost their kindred, friends, and property can never be offered any comfort or consolation. Though they are aware that any solution, abstraction or absolution is impossible to redeem them from their predicament, they sit back and analyse the root cause for their long malady. Yasmine Gooneratne revokes the past historical actuality that started the communal violence and converted the country into a sacrificial pyre.

Their independence from colonial rule never gave them an opportunity to merge various sects with patriotic feeling. In 1956 when Sinhalese was made the official language the sentiments of the Tamil were hurt which led to the radical view of their political ideology; “see the first sparks of this hate/fanned into flame in Nineteen Fifty Eight” (17-18). The malice and ill will continued to spread like fire and resulted in the “Big Match fever” – the incident of 1983 when an attempt was made to annihilate the Tamil minority from the country.

The local people live in constant fear and their situation is traumatic. Every day ends with curfew and dawn starts with new game of violence. They keep vigil night and day to safeguard their lives. Lack of security and lack of faith in humanity turns them desperate and addicted to alcohol. The situation turns them paranoiac for they are tugging at the threshold of death. Amidst the chaos of nihilism there still lurks a ray of hope that humanism would bloom. The Sinhalese and Tamils continue their friendship in spite of the politically incited hatred. as though we are neighbours still as we had been in ‘Fifty Eight,’

‘Thanks, by the way, for ringing.

There’s nothing you can do to help us, but

it’s good to know some lines haven’t yet been cut.’(42-45)

Jaffna, once a land of beautiful landscape has been turned into a battle ground. The poetess laments that“…landmarks of our childhood / curl like old photographs in the flames” (48-49). Young boys instead of empowering the nation by useful enterprise lay down their precious life for political doctrines. The sight of dead bodies strewn on the streets had become a common sight in the violence prone area. They have no time to spare, to stand and stare at the deceased for their life is at stake.

The joys of childhood, friendships of youth

ravaged by pieties and politics,

screaming across our screens, her agony

at last exposed, Sri Lanka burns alive.(57-60)

CONCLUSIONS

Gross human rights violation, radical power politics, legitimized terrorism ravaged the nation to shreds. The agony and anguish of the nation was exposed to the world through the poignant literary works. In spite of international involvement, peaceful co existence remains a farfetched dream. With the expectation that her poetry might act as a panacea for the troubles insinuated by separatist mentality and would bring peace to the war ravaged country.

|

Download the note on An Analysis of the poem bigmacth 1983of the Poem here.docx Size : 14.367 Kb Type : docx |